2018 was a special year for us as we celebrate our 50th Anniversary. We marked this hugely important milestone with a retrospective of our members' most iconic images at a public exhibition over a period of six weeks at the lobby of One Canada Square.

The exhibition, curated by Zelda Cheatle, presented a collection of images that define 50 years of the AOP, selected to illustrate the impact, diversity and quality of work by its members since 1968, who have included David Bailey, Lord Snowdon, Barry Lategan, Patrick Lichfield, Giles Duley and Nadav Kander. Their work will have been seen by the public the world over, from iconic images of celebrities and stars like Twiggy, in major advertising campaigns and countless car manufacturers, as well as documenting some of the world’s turning points, including wars, famine and humanitarian disasters. Many of their images have defined a generation, and helped to shape public opinion and create change.

Please scoll down to view the exhibition images, read about the history of the AOP and stories from our members.

AOP50 Image Gallery

All images featured in the AOP50 exhibition. Curated by Zelda Cheatle. ©Cornel Lucas

View Image Gallery

© Alan Brooking

Overview

AOP History 1968-2018

1968-1977

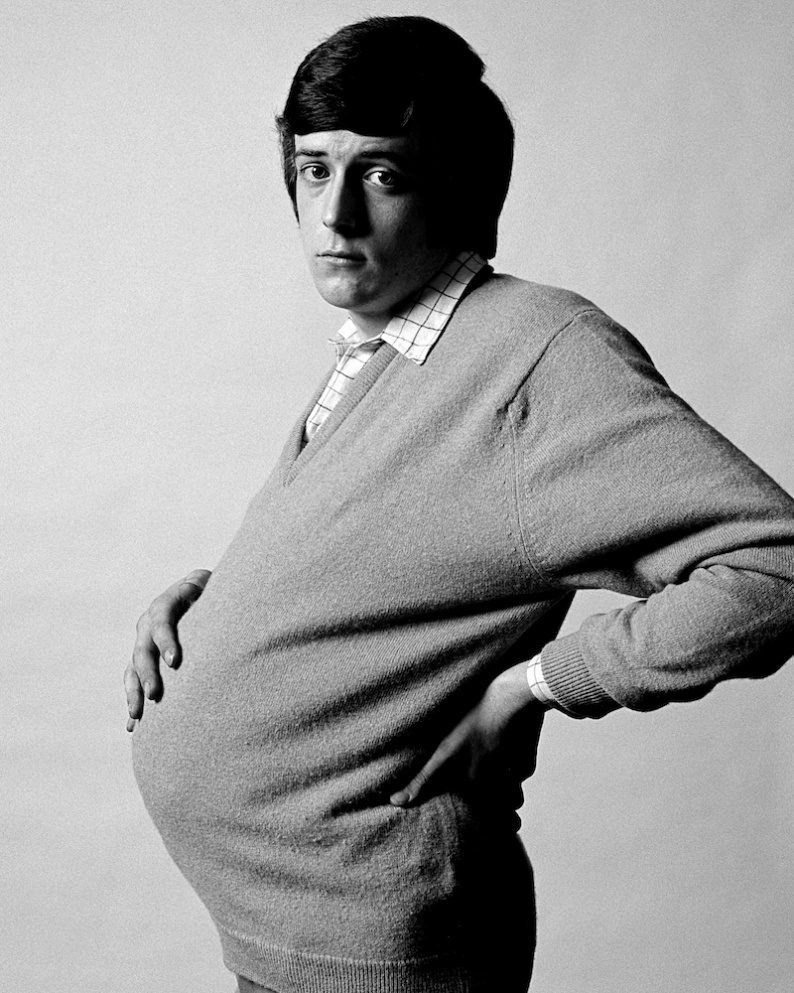

Stephen Coe

The 1960s saw a decade of remarkable change in the cultural scene and photographers like us flourished in ‘Swinging London’ but not so easily in 1970s.

Against all odds, the most unlikely of ‘non-joiners’ — a bunch of mostly fashion photographers — all rivals, linked up with those slightly ‘madder’ advertising photographers, plus ‘saner’ editorial photographers, to campaign as a group.

AFAP was initially formed to counter the ambitions of ALMA, a model agencies group’s cheeky intention to bill our clients direct; thus side-lining those photographers hiring them. Realising there were many other issues to tackle, we soon brought in the editorial photographers to become the new ‘E’ in AFAEP — for the next 20 years. We launched on 6th February 1969 and a full committee was elected at Kensington Town Hall. Most attending were bemused other photographers looked so strange — some in smart suits, others with longer hair in Levi 501s and Afghan jackets.

Soon Nan Winton and later on Tina Stapley became Administrator and the outward face of AFAEP — dealing with government, the IPA, ALMA and SLADE. SLADE had wanted to unionise pre-press and levy costly stamps on our work.

Under existing 1911 & 1956 Copyright Acts, copyright had always remained with commissioners regardless of whether any payment was made to the photographer. In 1973 Susan Griggs set out to challenge this. Over 15 years of arduous meetings, we fought to entitle photographers to copyright in their own work, as originators — on a par with authors, artists and composers. AFAEP soon led in professional photography, covering the elite in print media, music biz, fashion, magazines & ads. Standards of practice were agreed first in brochures produced jointly with IPA & new model terms.

As the 70s rolled on, popularity increased with regular AFAEP workshops and magazines.

Because I’d long felt photographers were hardly acknowledged in D&AD, I proposed we should organise our own Awards and it just took til ’83 to actually happen, opening in Hamiltons.

1978-1987

Alan Brooking

Our second decade was off to a good start with our arrival in central London — a little office behind a Covent Garden colour lab.

As Chair at the ‘80 AGM, I tabled a ‘Five-Year Plan’ to inject new life into the Association: We would set out to buy our own property, putting an end to renting. It was carried unanimously. First with Bryce Attwell, and then John Timbers in the Chair, we made it in four — moving into our first freehold in Domingo Street, Clerkenwell in December ‘84.

1983 saw the inauguration of our own Annual Awards. This was no easy project, it would take many years before becoming firmly established. But it’s hard to overstate the impact it was to have on public awareness — not just of members’ work, but of the very significance of our Association.

In April ‘85 after giving us ten years of amazing service, Tina Stapley left us. This was quite a shock to our system. But her assistant Janet Ibbotson was to take Tina’s place most ably — one of AOP’s most effective managers. Janet worked tirelessly (and successfully) at the seemingly impossible establishment of proper copyright law.

In ‘86 we proudly opened ‘The Association Gallery’ — something we’d dreamed of for years, with our Valerie Lawton becoming its first administrator.

1988, and AFAEP — quite a mouthful to pronounce in full but usually called ‘AFAP’, came to be known as The Association of Photographers.

1989. Our 21st Birthday! And like a timely birthday present, The Copyright Act finally passed into force.

1988-1997

Janet Ibbotson

Having won the war to establish copyright for photographers we then had to win the peace and establish business practices to respect these newly established rights.

So our third decade began with the chink of a single pound coin, being offered to photographers in an attempt to circumvent their rights, this act however only served to focus their minds on the need to get serious about business (the peppercorn was turned down!) and with the help of a small band of influential art buyers the AOP developed and established guidelines that have since become standard across the advertising industry and in many other countries too.

These standards were embodied in our groundbreaking publication “Beyond the Lens”. Originally thought of as a teaching method to stop the problems faced by young photographers leaving college, it grew to become the industry bible containing everything needed for working photographers, as well as industry entrants. It is still one of the great achievements of the Association.

So we won our copyright, established good business practice, worked with Pyramide Europe to fight for artists’ rights in the EU, joined DACS for secondary rights and brought photographers together with Shot Up North. We also massively increased the respect for photography with the exposure from our own gallery, the Awards and SUN, celebrating commercial, and importantly, personal work, so that by the end of this period the Awards ceremony attracted 2000 souls to the Barbican. And then we were as prepared as we could be for the digital future.

1998-2007

Richard Maxted

The decade from 1998 to 2007 was, for The AOP a period of consolidation.

By now, due to all the hard work that had gone before by the staff and members, ‘Beyond the Lens’ was established as the mighty tome of best practice. The gallery was hosting amazing shows which enjoyed huge footfall. Image magazine was frankly stunning. The education department was engaging thousands of students. The Awards just seemed to get better and better.

The biggest challenge The AOP faced came not from the activities we did, but from the way in which the members worked. The Digital Revolution arrived.

Finally digital could match film. So that was that, why shoot film. We all moved, en masse, to pixels, as opposed to grain. Nothing wrong with that, we’re photographers, we have the eye, the vision. We also had a lot of fax machines to sell.

To start with the effect on The AOP didn’t really register, the change took place and everything carried on. An area that did notice the change though was the film manufacturers, the amount of money we used to spend a year on film and polaroid was staggering, this money was now being pushed to digital kit. Over the years we’d enjoyed lots of support and sponsorship from these companies, those budgets were now being cut. To coin a line from a band of the time we could either ‘Look back in anger’ or ‘Roll with it’.

We rolled with it. New sponsors in the form of digital companies and re-touchers were sought. Money was invested in the website. The computer system at Leonard St was overhauled. Hindsight is of course a wonderful thing but the change was so massive there was simply no knowing how huge the effect would be on the industry or The AOP. Looking back on this time period, a friend of mine once said, ‘The bubble hadn’t burst, but certainly changed shape.’

What would the next 10 years bring?

2008-2018

Steve Knight

Our fifth decade started with new challenges, as the industry was embracing changes from film to digital, the global financial crisis was affecting both our members’ livelihoods and our industry.

The AOP also had to battle this storm, we like so many others had to realign our business, dramatically reduce our costs and look to ways to save money. We sold our beloved Leonard Street headquarters, which meant we had a small nest egg, this allowed us to move a little further north to river side offices in Downham Road, Haggerston, debt-free but with a lot to do…

The search for a new person to lead the Association was started, Seamus McGibbon, our current Executive Director was found and with him came a great new team, with input from the Board and AOP members we started the process of building on the AOP’s previous success.

We moved again, back to our roots and to the home of photography — Holborn Studios. But we kept our little nest egg Downham Road, which continues to grow, providing us with additional financial stability.

Over the last four years the AOP team has worked hard to develop new membership categories and services that reflect the modern image making industry and acknowledges the journey creatives make through their careers.

The AOP Awards were reborn, now including both the Open and Photography Awards at a new home, The Truman Brewery in East London. By 2018 they had grown to become the photography event of the year for both commissioners of photography and photographers alike.

I am so proud to be associated with and to serve the AOP and its members. It is such a special establishment that will, I am sure, thrive for another fifty years at least.

Curator Interview - Zelda Cheatle

|

|

Stories - Janet Ibbotson and the AFAEP Girls

Janet Ibbotson and the AFAEP Girls

As part of AOP50's celebrations we've been talking to key individuals instrumental in shaping what AOP is today. Janet worked for AOP for many years both as General Secretary and later on as Managing Director. As one of the original AFAEP girls, Janet worked tirelessly for the AOP and on behalf of photographers. We caught up with her to hear about the early days and particularly about the role of women in the association.

©Tessa Traeger. Hommage to Monet

How did you first get involved with the AOP?

I was an art buyer at McCann Erickson in the early 80’s and made a silly move into print buying. I wasn’t enjoying the new role or the lads culture that went with it. When a photographer’s agent told me about the AFAEP (now AOP, of course) job I jumped at it. AFAEP’s office was on the ground floor of an old drafty high ceiling’ed warehouse at 10 Dryden Street, with only one small window above head height and a too close neighbour involved in publishing porn . There was a large stationery cupboard and kitchen at the back, a partitioned space for the boss, typewriters, an old photocopier and a large open space with tables for desks which was office, meeting room and workshop space. Covent Garden itself was then a run down area housing photographers’ studios, film processors and black and white printers and AOP’s office was a popular spot for anyone dropping off film, waiting for prints, or in need of somewhere to spend their lunch break. The boss was Tina Stapley (later Golden), daughter of the redoubtable Nan Winton. Jane Hampshire was the other member of staff. Noelle Pickford left a couple of months before I joined. I was there partly, I think, to replace Noelle and I was given the grand title of Assistant General Secretary. We lived and breathed AOP.

Through the Booking Service we kept diaries and made bookings for a select group of assistants. There were no mobile phones so the Message Service - noticeboard, pagers, telephone and message taker - provided assistants, stylists, home economists and others with a means of staying in touch with photographers. Both provided an income for the AOP but were run primarily to serve photographer members. With no internet, the sourcing of other services was by word of mouth or through the ‘phone book, so the office also maintained card indexes of recommended services and a “source” book - hand written - of more obscure items indexed by keywords which we had to remember. We prided ourselves on tracing new services or finding the unfindable. It was time consuming work and disruptive as calls were constant. Each staff member had other tasks, such as fundraising, campaigning, arranging workshops (sometimes at Dryden Street but often at Holborn Studios), organising committees and large unruly meetings, as well as the more general management and administration of AOP. The first big project I was entrusted with, was the Magazine Action Group (MAG), working with a committee of dedicated photographers intent on improving terms and conditions and establishing a minimum rate for editorial photographers. The work ranged from regularly mailing 150 photographers to negotiating with publishers and their lawyers. It was not without difficulties - I was hauled over the coals by the Office of Fair Trading for forming a cartel. Negotiations were difficult, particularly with IPC, which at the time was the biggest magazine and journal publisher in the UK and there were uncomfortable talks with NUJ officials who thought AOP was trying to muscle in on its territory. We eventually had some success and a Minimum Economic Rate was established. For me, it was the best possible training ground for subsequent work on standards for advertising photographers, for campaigning on rights and for my later career in copyright.

Tell us about the AFAEP girls and women in the AOP

Tina fought tirelessly for the AOP. With the Council, she started the AOP Awards, raised funding and then oversaw the move to Domingo Street. We were all involved in the work but Tina led. Her positive, can do attitude was an inspiration. She taught me respect for my abilities and to work and play hard. We were known as the “AFAEPy’s" a term that may seem patronising now but I have used it recently to describe someone, normally a woman, with a particular approach to their work, that is someone who will turn their hand to anything, with an open and enquiring mind, with common sense and an ability to work in a team and prepared to share credit for their successes.

After Tina left, I took on additional responsibilities for organisational matters and then some time in the mid-80’s, I was asked to take over as General Secretary. It was at about this time that copyright started to become a real issue for photographers and members were in increasing need of advice and legal services. These later became my focus but first there was a financial crisis to deal with. Keith Johnson Photographic helped pull us out of the mire and also sent Gwen Thomas to join AOP as its first full time financial person. Gwen's sympathetic approach, kindness and loyalty are legend and she remains a close friend. Her qualities also meant that members very quickly turned to her for help and so her role expanded. Some years later she took on the copyright and legal role and ended up as Company Secretary, from which role she retired in 2015. Valerie Lawton joined AOP from the Hamilton Gallery and made a huge success of the AOP Gallery. Under her supervision the Awards came into their own. Val with Gwen later ran the organisation. Jackie Kelley was smart, efficient and having trained as a photographer had good design skills. Jackie successfully re-made Image Magazine and she also oversaw other AOP publications. Jill Anthony joined and her brief to look after the assistants and services expanded to include education. She built up AOP’s relationship and reputation with photographic colleges and managed the Beyond the Lens project.

I left AOP in 1992 to follow a career in copyright but was invited back to run the AOP again as its Managing Director and stayed for two years between 2005 and 2007. These were difficult years with a crisis at AOP with technological change beginning to make its impact felt on the photographic profession, but also impacting on the way in which the AOP had developed its services. Previously successful projects were becoming obsolete or had become money pits or administrative millstones I had the support of Gwen as Company Secretary and Michael Harding as a dedicated Chair working with an excellent Board but it was not an easy time. Three notable staff members during this period, apart from Gwen, were Ella Leonard who took AOP work on education and training to another level, Anna Roberts and Rachel Rogers who ran the Leonard Street Gallery and the Awards.

Women photographers during my time were few and far between but Tessa Traeger and Tessa Codrington were top class. As was Sandra Lousada - a great photographer, a real role model for others and also owed much by the AOP. Julie Fisher, Jess Koppel and more recently Carol Sharp were all excellent photographers who also worked tirellessly for the AOP.

Tell us about some highlights during your time with the AOP

I tried to avoid copyright as long as I could until Mike Laye persuaded me it was fundamental to the fair treatment of photographers. I then threw myself into it wholeheartedly. By the mid-80’s I was Secretary to the Committee on Photographic Copyright, a cross-photography organisation, which campaigned for changes to photographic copyright. I did much of the donkey work but was part of a lobbying team with Susan Griggs of BAPLA, Anne Bolt of the NUJ and others. I persuaded AOP members to take an active role in the lobbying campaign and once committed there was no holding them back - they wrote and met and argued with their MP’s and peers and became crucial to our success. Susan and I made our case to Tony Blair (he led for the opposition during the committee stage of the Bill) on the need to except photographs from the news reporting exception - this was subsequently achieved. We were helped by Lord Brain of the RPS - a godsend for our campaign as most of the debate took place in the House of Lords - his personal project was to ensure holograms appeared in the definition of a photograph. Our crowning success was the removal of the section of the 1957 Act that granted copyright in commissioned photographs to the commissioner.

The Act came in on 1st August 1989 and the advertising agencies finally woke to the change.

What cultural changes did you witness during your time at the AOP?

Increasing numbers of women coming into photography but many did not stay. This was still the case in the mid-2000’s I don’t know if it still is now.

Back then you were an advertising still life photographer, or a food photographer or an editorial photographer or an “art” photographer: put into silos. I think that has now gone (to a large extent) - maybe the Awards helped.

Who are your standout photographers, and can you tell us about some iconic images?

The standout photographers for me are the ones who dedicated their time to working for the AOP or to campaigning on its behalf: those who immediately come to mind are Alan Brooking, Robert Golden, Geoffrey Frosh, Frank Herholdt, Rob Brimson, Laurie Evans, Mike Laye, Martin Beckett and Michael Harding but there are oh so many more.

I’m a fan of black and white photography so Ansel Adams, Bill Brandt, Edward Weston, Alfred Steiglitz and Edward Steichen, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Eugene Atget come immediately to mind.

Stories - The beginnings of the AOP by Bob Croxford

Sometime in the mid 1960s an official from ASMP in the US visited London, and a small meeting organised by Ann Bolt of the NUJ was held in a London hotel. So few turned up that we could all sit comfortably around one table in the lounge area. This meeting discussed, among many things, the limitations of the UK 1956 Copyright Act. This Act did not give photographers the same rights as other artists. There were some really silly anti-photographer clauses but most importantly photographers did not automatically own their copyright nor did they have the right to negotiate the terms of sale.

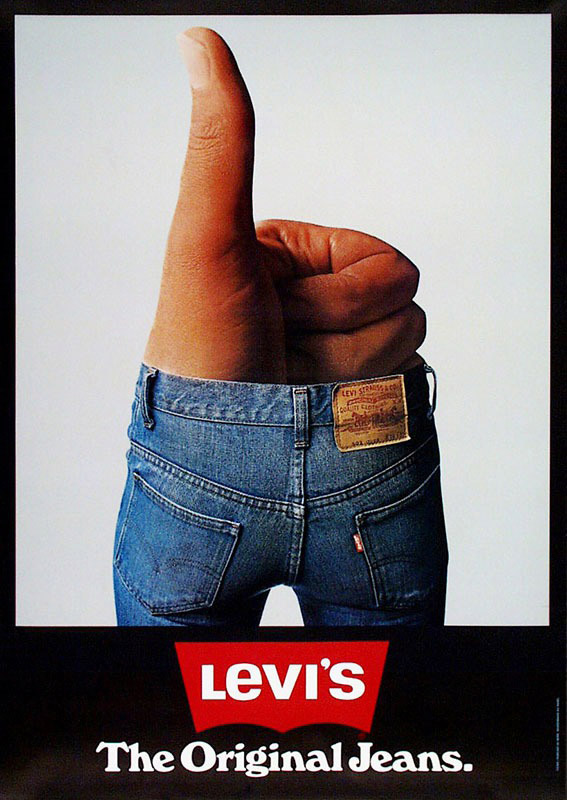

©Bob Croxford - European Levi campaign, 1977.

Myself and a couple of others, went away from the meeting with a determination to change the law. We spoke to a few other interested photographers but at that stage there was no real way we could proceed. Then a couple of years later an argument about models’ fees developed and a meeting of photographers was called. (Basically model agents were holding photographers liable for payment of fees and at the same time clients, including magazines and advertising agencies, were using photographers as a free bank by not paying those expenses until months later). Suddenly, a membership organisation was formed, which was made up of photographers who worked for commercial clients. We weren’t wedding photographers, portrait photographers or salaried technicians. We dealt in copyright and rights of reproduction.

Our small group of about four photographers interested in copyright issues became founder members of AFAP, as it was originally called, and started raising issues, which were of interest to us. Of course there were a lot of older and more experienced photographers in the Association who naturally formed the early committees. However there was an incredible spirit of co-operation and younger members were asked to help in various sub-committees. I worked in the membership committee for a couple of years before being elected to the main Committee in the early 1970s. Now I had my chance to start talking about copyright in earnest. We formed a Copyright Committee and set about deciding what we wanted to see changed. Then we had a stroke of luck. The Copyright Act was not due for review until 1981 but there had been an explosion in the use of photocopiers and suggestions were made that an adjustment should be made to the 1956 Act. Justice Whitford established a Government committee to consider proposals. AFAEP was ready. We already had our draft. I cycled across town and delivered our proposals in person. (This caused a bit of consternation in the Whitehall office because our submission was the very first. They hadn’t expected anyone to be so quick).

I later moved to Cornwall and passed the work over to others.

©Bob Croxford, The Cotswolds.

At the last minute The Newspaper Proprietors Association tried to introduce a clause allowing them to steal pictures ‘In the public interest’. This was resisted by a letter writing campaign to MPs. I was very surprised that my local MP did not agree with me and voted for the Newspaper Proprietors amendment - a motion, which they lost. Come the next election I campaigned hard for a rival candidate and he lost his seat!

When I look at the 1988 Act I can see that every single item of change, which I wrote and cycled across London to deliver, is now enshrined in Law.

Apart from work on copyright one of AFAEP’s major achievements was the agreement with The Institute of Practitioners in Advertising for a set of terms and conditions in 1973. These included a guarantee of one month payment, clear requirements for cancellation fees and many clauses which improved the working relations of photographers.

In those early days the Committee ran a highly respected Ethics Committee, which attempted to mediate, in complete confidence, in cases of disputes between photographers and clients.

Over the years AFAEP had several battles with Kodak over quality. In one notable episode they threatened to sue me personally over an article I wrote and published in the AFAEP newsletter. Fortunately they saw sense and by way of apology took several of us out to a lavish lunch and agreed to buy advertising space in the newsletter at double the normal rate.

AFAEP, in those early days staggered from one crisis to another, and it was only through the nerve of those early committee members who faced up bravely to insults, legal threats and financial difficulties that the Association survived.

AOP50 Member Slideshow

AOP50 Sponsor

We caught up with AOP50 sponsor Retoucher & CGI studio Bunker to find out all about them and why they're different.

Hello Bunker! Tell us about what you do

Hi! The best way to describe us at The Bunker is image makers. We combine our knowledge of photography and the way the world works to create beautiful and engaging imagery. Light, colour and perspective are the most important things you need to understand if you want to manipulate imagery, so we’re constantly analysing what we see around us because one day we’ll have to translate what we see into a live project.

How did you get into this business?

Its two fold: One side of our partnership came through the print/reprographics industry as an apprentice, scanning and retouching hundreds of transparencies at a time and learning different retouching techniques to make a very laborious process faster, more accurate and more enjoyable, learning from plenty of mistakes along the way! The other side was born out of a love for photography and a fascination of how to manipulate imagery. Two very different ways of arriving here but they give us a great breadth of experience and a unique approach to our work.

How are you different from other post production offerings?

Quality and reality is key for us and our approach is always calculated and considered from the outset of a project. That said, I think if you are passionate about something, an excitement takes over and your imagination can just run wild. The journey we’ve taken into the industry has also helped to make us different, we’ve honed our skills over many years which allows us to dedicate all of our time to giving our clients precisely what they want and more!

How closely do you work with photographers?

Very closely indeed, we’re often an extension of a photographer’s offering to their clients so developing strong relationships with them is important.

One of the things I have always enjoyed about this industry is the collaboration we have with photographers and the fact that we’re so like-minded. Stuff like working closely together on location to solve problems, sharing knowledge about processes, geeking out about kit and having someone to whinge about things with. It’s scary how similar we are as people!

What advice do you have for our photographers to make the creative process run smoothly?

There are so many images around us all the time it’s hard to differentiate yourself creatively, our thoughts are that creativity can also come from how skilfully you overcome some of the more technical challenges you face when shooting multiple elements for a scene.

Having a clear vision in your mind’s eye about the final composition will help you to get heights and angles, lighting and depth of field spot on and once you’ve mastered this, it will not only add more realism to your imagery, but it will begin to open up more possibilities, giving an extra dimension to your imagery.

Where do you see the future of photography?

I think the success of social media platforms like Instagram prove that we’re still very much in a visual culture and a huge desire to share photos, this does however, present the challenge of how to retain the integrity of a industry of professionals in an over-saturated whirlwind of imagery and that’s where I think the technical aspect I talked about before is important. The future’s bright for adaptable, knowledgable and likeable photographers who embrace new challenges and find evermore creative ways to overcome them.

Why is AOP50 important to you?

At The Bunker, our personalities mean that our first instinct is to help, even if it means we’re not the right option and we can’t help using our services. We enjoy giving advice and guiding people in the right direction and we understand the value of having a support network around you. Having a group of friends you can call on for support is important in any walk of life and that’s why we believe that AOP is such a valuable asset to any photographer, no matter how far into their career they are.